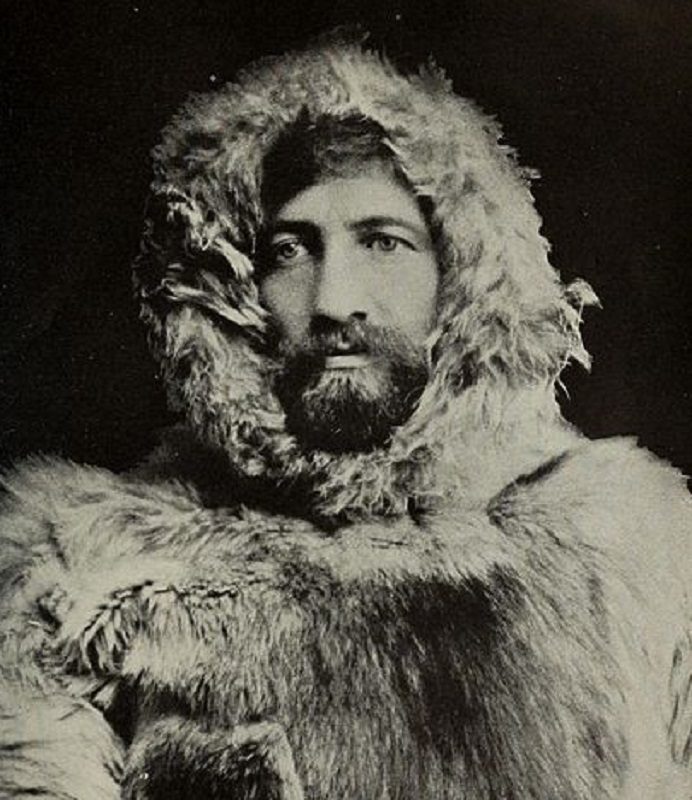

His name was Frederick A. Cook—a doctor known for his ingenuity and unshakable resilience. He claimed to be the first person to reach the North Pole and the first to climb Mount McKinley in Alaska. However, as history records, the discovery of the North Pole is attributed to Admiral Robert Peary.

Dr. Cook passed away in 1940 at the age of 75, largely forgotten and in relative disgrace. It’s no surprise that his memoirs are titled Hell Is a Cold Place. Learn more about the life of this legendary Brooklyn doctor and explorer on i-brooklyn.

“Good Spirits Replace Sunlight”

While few believed Dr. Cook’s claim to have reached the North Pole, his heroic rescue of 18 fellow explorers in Antarctica in 1897 is a story that has been widely accepted.

When their ship became trapped in the ice, Cook took charge during 68 days of total darkness. He insisted the crew eat undercooked penguin meat to prevent scurvy and made them spend an hour each day in front of the ship’s burning stove to combat depression.

His methods worked. Their health improved, and their spirits lifted so much that even Cook’s critics admitted that he was one of the first to recognize the connection between mood and sunlight deprivation.

However, his claims about Mount McKinley and the North Pole were met with skepticism.

On September 1, 1909, after an unexpectedly long return journey, Cook sent a telegram from the Shetland Islands, north of Scotland, announcing that he had reached the North Pole. Shortly after, Admiral Peary sent a telegram from Labrador stating, “I placed the stars and stripes at the Pole.” Peary’s claimed date of arrival was April 6, 1909, nearly a year after Cook’s alleged achievement.

The Battle for the North Pole

Within weeks of Cook’s return to America, the battle for the polar prize erupted. The press demanded proof from both men.

By the end of the year, Peary—who had stronger financial backing—was declared the winner.

None of Cook’s detailed descriptions of the smooth polar ice at 88 degrees latitude, which matched the observations of later explorers, nor his deep knowledge of Inuit culture and language, could change the tide in his favor.

Cook had also invented specialized ice goggles and tents to withstand Arctic conditions and designed sturdier sleds with the help of his brother Theodore, who tragically died after becoming trapped in a freezer in upstate New York.

A Passion for Collecting Arctic Souvenirs

Cook’s love for collecting artifacts from his expeditions delighted his family.

His grandnephew recalled spending time with Cook between the world wars. The explorer once brought home a walrus skull and another time gifted traditional Inuit children’s clothing to him and his brother.

When asked during a Poly Prep Country Day School exam in Brooklyn whether Peary had discovered the North Pole, Cook’s loyal grandnephew circled the word incorrect and wrote his uncle’s name in pencil instead.

Full Pardon by President Roosevelt

Despite his supporters, Cook had many opponents.

In his 1997 book, Cook and Peary: The Polar Controversy Resolved, Robert Bryce argued that Cook lacked the skills to take accurate astronomical readings, and that the ones he provided had been forged by a ship’s captain in exchange for money.

Still, Cook’s legacy had its defenders—including a society dedicated to clearing his name.

They even supported him in the 1923 fraud conviction, which alleged that Cook misled investors in a Texas oil scheme. However, Cook adapted well to life in Leavenworth Prison, working as a doctor in the prison hospital. He even described prison life as a “vacation island”—a fitting statement from a man who had endured freezing polar winters.

In the end, justice was served.

In 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt fully pardoned Dr. Cook of all charges, restoring his name, though his legacy remains debated to this day.