In the 19th century, midwifery in New York and Brooklyn was given over to the emigrant and to the aboriginal women, the indigenous inhabitants of America. This profession was acceptable to these categories of women because it was almost the only one female job, which gave a chance to earn a living. Midwives helped with childbirth, acted as general practitioners for women and children and performed abortions. In the last years of the 19th century, midwifery came under attack from medical professionals, who began to insist that only licensed doctors should do this.

In 1906, Frances Elizabeth Crowell, a renowned nurse and social worker who devoted much of her life to improving the education and standards of nursing in New York City, conducted a study of local midwives. She concluded that fewer than 10 percent among them were true professionals with the necessary qualifications and skills. She also suggested that all midwives performed abortions. This report was the end of midwifery. Read more about the development of midwifery and its problems in 19th-century Brooklyn on i-brooklyn.com.

Midwife-assisted childbirth

Childbirth in the 19th century was a dangerous procedure. Women regularly contracted puerperal fever, an infection of the uterus that could lead to sepsis and death. Many women who gave birth suffered from postpartum haemorrhage. This heavy bleeding, if left untreated, could even be fatal. Some young mothers suffered from eclampsia, a condition in which blood pressure rose rapidly and could cause fatal convulsions. In 1900, six to nine women died for every 1,000 births. This was 30 times higher rate than today.

In this situation, midwives took over the childbirth. The story of midwives in the 19th-century Syrian colony of New York is illustrative. Of more than 500 births, only seventy-three babies have been recorded and only sixty of them provide information about the assistant of the midwife. Just over half of these cases were attended by Syrian midwives, the rest by professional doctors, either at home or in nearby hospitals, who were much more likely to register births than midwives. Since the vast majority of unregistered births in New York were performed by midwives, this significantly underestimated the number of babies born.

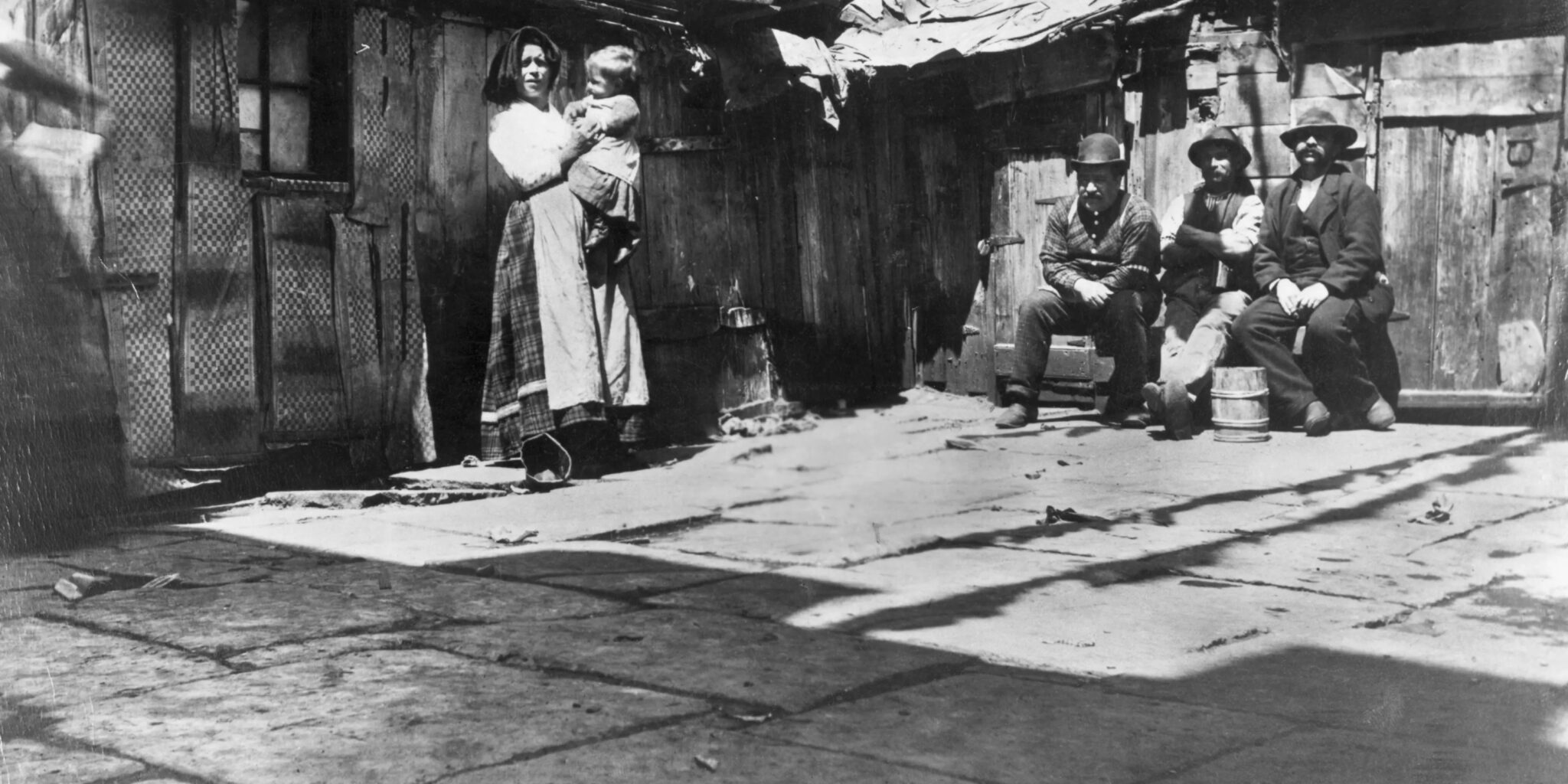

It was especially difficult for the poor to give birth. Fewer opportunities for safe childbirth in 19th-century Brooklyn were available not only to poor women but also to those who were abandoned or unmarried. Many of these expectant mothers, as a rule, gave birth in train stations, where they were given shelter. Then, there they abandoned their child, hoping for the kindness of strangers.

Brooklyn maternity hospital

Such children were called foundlings or almshouse cubs. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle was full of sad articles about such babies. Concerned doctors and citizens saw the need for hospitals for babies and expectant mothers, where training programs for nurses would be conducted. One of the first hospitals in the city and in the state of New York to initiate these programs was the Brooklyn Maternity Hospital (originally the Brooklyn Homeopathic Lying-In Hospital).

The hospital changed its name several times to reflect the changing needs of its patients. The principles of its work did not change and were very simple. They helped the homeless, saved the fallen, cared lovingly for the little ones left alone, sailed with the flow of life, subjected to all its adverse currents. They also prepared brave and strong, gentle and true women to enter homes and serve at the bedside with intelligent care and concern. These were the principles of the Maternity Hospital, which were carried out.

In addition, the conditions of admission to the Brooklyn Maternity Hospital stated that they would never refuse help to a patient because of lack of money. In return, the institution asked them to trust them so that the doctors could provide qualified care. Regarding payment, the hospital figured out how to resolve this issue so that both the help could be provided to the woman and the hospital could get something from it. In the case of free care, the patient who gave birth and recovered after childbirth was obliged to work for three months as compensation for medical care.

The Brooklyn Maternity Hospital believed that after a qualified person had helped an unmarried woman during and after childbirth, she would no longer need similar services under the same circumstances. The maternity hospital depended on charitable donations and private funds. They believed that they provided not only material but also spiritual assistance to a woman in difficult times, saving her from poverty.

The hospital held benefit dances and tea parties to raise money for medical supplies and drugs for such necessary procedures as surgery, as well as for more beds and cribs for infants. In 1930, the hospital changed its name to Prospect Heights Hospital, by which time the maternity ward had been incorporated into the hospital as a whole.

Home nurses

While special children’s hospitals had transformed the lives of many Brooklynites and saved countless lives, the idea of training home nurses was becoming popular in the United States. In 1888, when Brooklyn was hit by a smallpox epidemic and a severe blizzard, the hospitals were overflowing with sick and dying patients.

Many poor people were dying without care on the streets and in train stations. Thus, thirteen caring Brooklynites met at the home of Dr. George R. Fowler, a prominent Brooklyn physician, to discuss his profound shock at the unpreparedness for outbreaks of disease and the ignorance of basic hygiene during illness.

Dr. Fowler was particularly interested in home nursing, having spent much time in Europe and seen its positive effects. This community group decided not only to continue visiting neighbors and friends but also to take a step further by training nurses to visit the homes of the sick and poor. Thus, the Brooklyn Red Cross Society was formed.

The Society’s initial mission was to focus on maternity care and providing care to the sick and poor. On the first visit, nurses accompanied by a physician visited the homes of young expectant mothers to provide prenatal instruction. Six weeks after the birth of the child, the nurse would return without a physician. This was a revolutionary step at the time.

Philanthropist’s help

These visits were usually free to the patient or for a very nominal fee. The nurses taught the new mothers how to provide proper hygiene, bathing, medical care and nutrition for their newborns, as well as how to care for themselves before and after childbirth.

The Visiting Nurse Association of Brooklyn was initially a not very successful idea. It relied on charitable donations, bake sales, dances and musical evenings. Then, the famous Brooklyn philanthropist Alfred T. White stepped in and promised to pay one of the nurses’ salaries for a year if she would visit the homes of young but poor mothers. Thus, it all began.