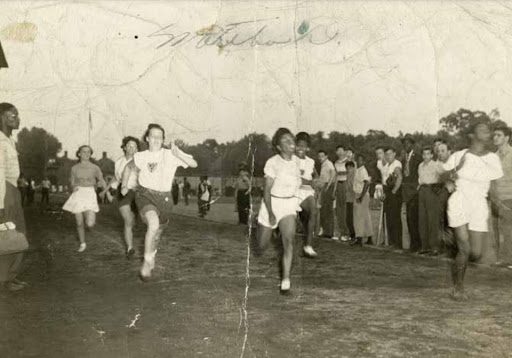

Mary DeSossour Sobers built an impressive collection of gold and silver medals, marking a remarkable journey in which she broke barriers in athletics. She became the first African American girl to compete in the Police Athletic League (PAL) games at the 13th Regiment Armory in Brooklyn.

Her first opportunity to race came at the age of 13 in August 1945, when sheer curiosity led her to the armory. Running her very first race in a long green-and-beige dress, her sister’s small-heeled shoes, and galoshes over them, Mary defied all odds. Years later, she would laugh at the memory.

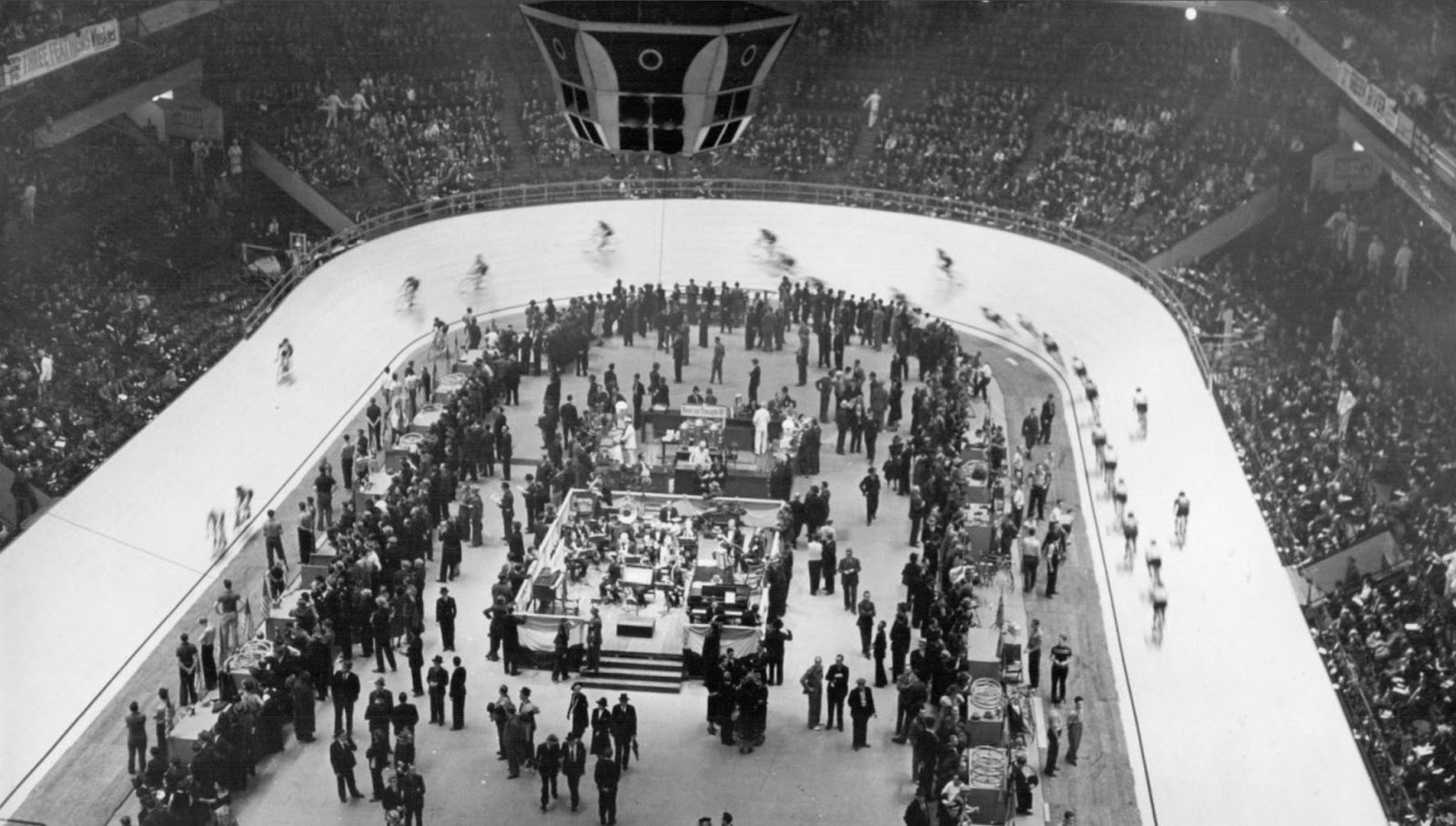

Despite her unconventional race attire, Mary’s second-place finish qualified her for a 40-yard sprint at Madison Square Garden two months later, where she won gold. Alongside her twin sister, Martha DeSossour Sobers, Mary would go on to win many more races. In 1946, they became the first members of the Trailblazers, Brooklyn’s first African American girls’ running club. More on i-brooklyn.com.

The First Race

Born on December 22, 1931, in Eutawville, South Carolina, Mary grew up in Brooklyn with her parents and her twin sister, Martha. Her entry into the world of competitive sports happened purely by chance.

One morning in August 1945, the sisters were sent on an errand to buy groceries. That day, a bus ride took them to the nearby 13th Regiment Armory, where they saw a crowd gathering inside. Curious, they entered, thinking they might find a circus show.

Instead, they discovered a track and field competition. Officials invited them to join the race. While Martha hesitated, Mary stepped forward, insisting she could run, despite wearing a dress and galoshes.

After some hesitation, an official reluctantly agreed to let her compete. Against all odds, Mary won—making history as the first Black girl to compete in an official track event in New York City.

That day, she won three qualifying races, securing a place in the citywide track meet scheduled for a few months later.

Sitting in the balcony above the track, Martha overheard the crowd murmuring:

“Who is that little Black girl? Where did she come from?”

Years later, she recalled how unusual it was to see a Black athlete in a competition like this.

Qualifying for the City Championships

Mary’s victory in the preliminary rounds earned her a spot in the finals at Madison Square Garden. However, despite crossing the finish line first, she was only awarded a silver medal.

The gold went to a white girl, who had actually placed second. The reason? Mary hadn’t provided the necessary registration documents.

While unfair, her parents saw this as an opportunity to challenge segregation in New York sports. They knew it wasn’t just about Mary running at Madison Square Garden—it was about changing perceptions of what Black girls could achieve.

Determined to ensure their daughter had a fair chance, Mary’s mother, Hattie, took her on a shopping trip to Broadway Avenue in Brooklyn, a major retail district in the 1940s.

She bought proper running shoes and a green jumper—the standard sports uniform for girls at the time.

More importantly, she took Mary to the hairdresser.

Hattie understood the racist stereotypes many white Americans held about Black girls and women. She wanted Mary to look polished and respectable—as prepared as any other competitor in Madison Square Garden.

Her hope was that every successful Black girl could dispel the ugly narratives that had long marginalized African Americans.

On February 15, Mary prepared to step onto the track, not just as a 13-year-old girl, but as a symbol of Black excellence.

Overcoming Doubts

As she arrived at Madison Square Garden, Mary was overwhelmed by the grand stage.

Moments before the race, Officer Jack, a PAL official, stepped in. He helped her submit her registration papers and attached her race number to the back of her green jumper.

Pointing to the gold medal on the winners’ table, he said:

“That one is yours. Today, you’re winning gold.”

Mary hesitated. Could she really win?

Jack, sensing her doubt, encouraged her to jog around the track, just like the other girls. She didn’t know why warming up was necessary, so he explained:

“It loosens your legs before the race.”

Then, he gave her final instructions, as she would be in the first heat.

“I have high hopes for you today,” he told her.

The Fastest Girl in New York

Mary wasn’t the only Black girl in the competition that day, but she was one of only two competing in the 40-yard sprint.

Her biggest rival? Edna Colon from Brooklyn—the same girl awarded gold at the previous race in the 13th Regiment Armory.

Joining them were competitors from Manhattan and the Bronx. Weeks earlier, thousands of girls had raced in regional qualifiers, but only the fastest had advanced to this final round.

As the race began, Martha watched from the balcony, anxiously clutching their mother’s hand.

“Will racism play a role again?” Hattie wondered.

She refused to sit at the edge, fearing that her excitement might send her over the railing. Instead, Martha provided play-by-play updates, cheering loudly as the race unfolded.

Mary was slightly faster in proper running shoes than she had been in heels and galoshes.

She blazed down the track in just 5.4 seconds, leaving no doubt—Mary DeSossour Sobers was the fastest girl in New York City.

Making History Beyond the Finish Line

Mary’s victory wasn’t just personal.

Her talent and dedication, along with her sister Martha’s, helped establish the first sanctioned track and field league for African American girls after World War II.

In 1948, Mary and her teammates in the Trailblazers trained for the London Olympics—but that’s a story for another day.