A little more than a century ago, Brooklyn faced one of the largest epidemics in history. It was known as the Spanish flu and infected a third of the world’s population, killing nearly 50 million people and forcing New Yorkers to stay indoors and wear masks. The city’s response was similar to the measures it has recently taken as COVID-19 raged around the world. All of them were believed to slow down the spread of the epidemic in 1918 and included fighting to keep schools open, building seasonal hospitals and enforcing home quarantines. Exploring that epidemic shows that Brooklyn, as part of New York City, has a well-established public health system. It is known for successfully slowing the spread of infectious pandemics, such as yellow fever, cholera, typhoid fever and polio. Read more about the 1918 epidemic and how it was overcome on i-brooklyn.com.

The Spanish flu that wasn’t from Spain

In 1918, while America’s focus was on World War I, the world was gripped by the most devastating pandemic of modern times. The 1918 flu pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu, swept across the globe in 1918–1919, infecting a one-third of the world’s population or 50 million people. The Spanish flu was caused by the H1N1 virus, which contained genes from birds. There is still no conclusive evidence of the geographical origin of the strain. Thus, the place of the outbreak remains a mystery.

Contrary to popular belief, the flu did not originate in Spain. When the outbreak began in Europe, wartime censorship suppressed any possible reporting of the epidemic. This was done to maintain morale. As Spain was one of the major European countries that remained neutral in World War I, information about the growth and spread of the disease was not censored and was freely shared. As a result, it was perceived that Spain was hit harder than other countries and that the flu had started there earlier than anywhere else. This led people to believe that it had started in this country.

New York City was hit the hardest by the epidemic in the fall of 1918. In the absence of a vaccine or treatment, the city’s approach was to rely on its well-established public health infrastructure. Drawing on lessons learned from previous outbreaks of cholera and tuberculosis, New York City adopted a containment strategy. The city’s proactive approach had three main goals: to slow the spread by distancing the healthy from the sick, to launch a massive education campaign to educate people about how the virus spreads with the best practices for avoiding it and to provide surveillance capabilities.

Strategies for combating the disease

By October 4, 1918, Brooklyn had reported 421 cases of influenza. Thus, began the public health crusade to stop the spread of the disease. On October 10, the military installation Camp Mills on Long Island was quarantined. The coal mines of Pennsylvania were also closed as the places of employment and hotspots of infection. Although the entire coal industry was alarmed by the enormous drop in production, it managed to mobilize medical personnel to support sick people.

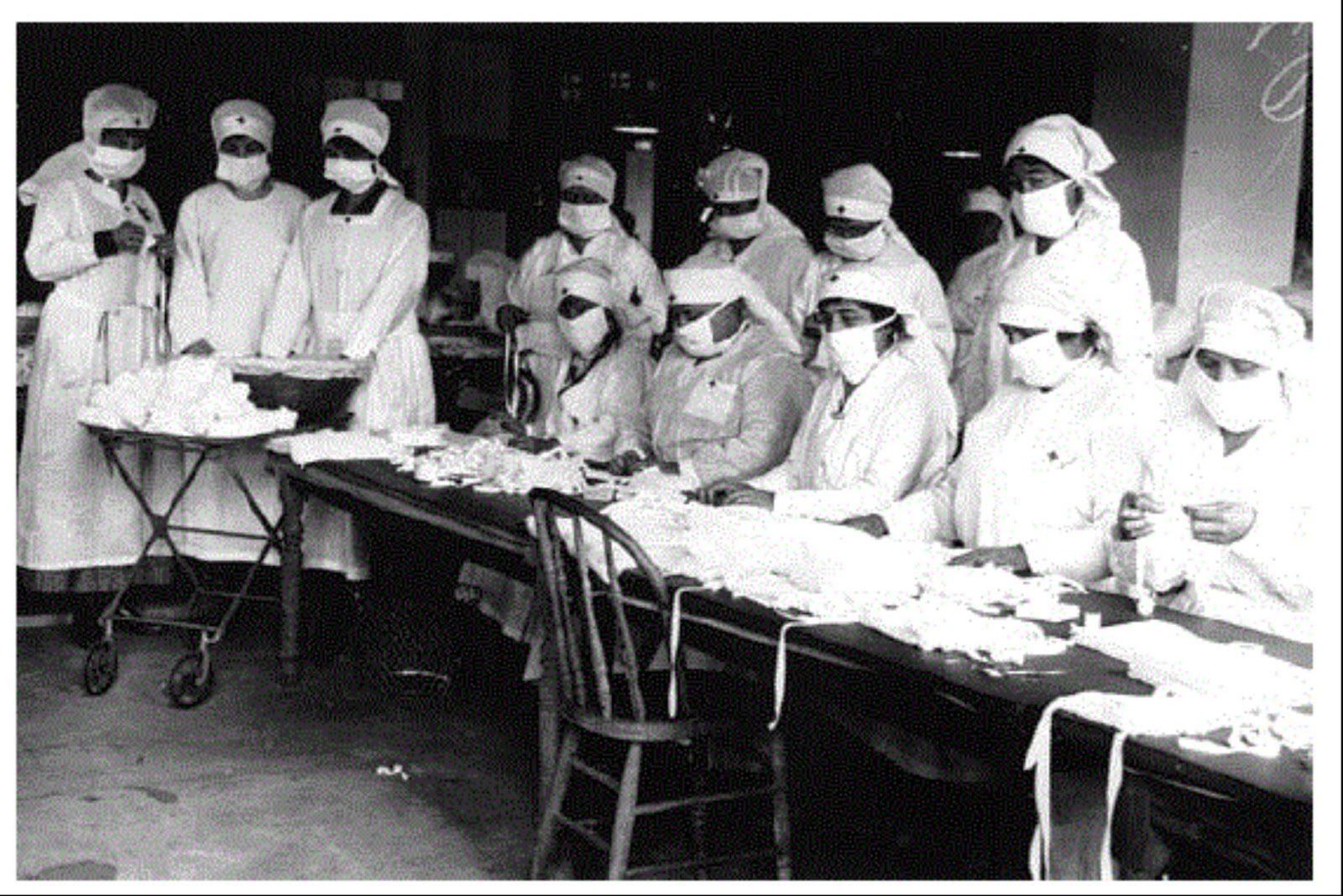

According to The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, as of October 20, 1918, there were approximately half a million cases of the disease in New York City. The Health Department quickly developed and implemented new strategies to combat the epidemic. Brooklyn was divided into twenty-four boroughs. Medical personnel were assigned to support each of them. In addition, each of these boroughs provided inexpensive prepared meals to sick residents.

It all happened very quickly. On September 18, 1918, no one could have imagined that an epidemic would occur at all. On October 4, there was a sudden surge in cases. By October 25, local health authorities announced that the worst was behind. By November 1, the infection rate had dropped significantly. It is known that there was a whirlpool of misinformation surrounding the epidemic. Thus, one local swimming coach suggested that nothing more than overeating could be partly to blame for the epidemic. There was also an advertisement in the local newspaper for one of the companies that suggested that spinal correction was needed to avoid contracting the virus.

Public health system

There were some mistakes made by Brooklyn’s public health system. There was a famous case, which was reported in the local press. After the peak of the epidemic had passed, the local Red Cross decided to throw a ball for 500 people. However, lemonade and fruit punch were served to the guests using a total of fifteen glasses.

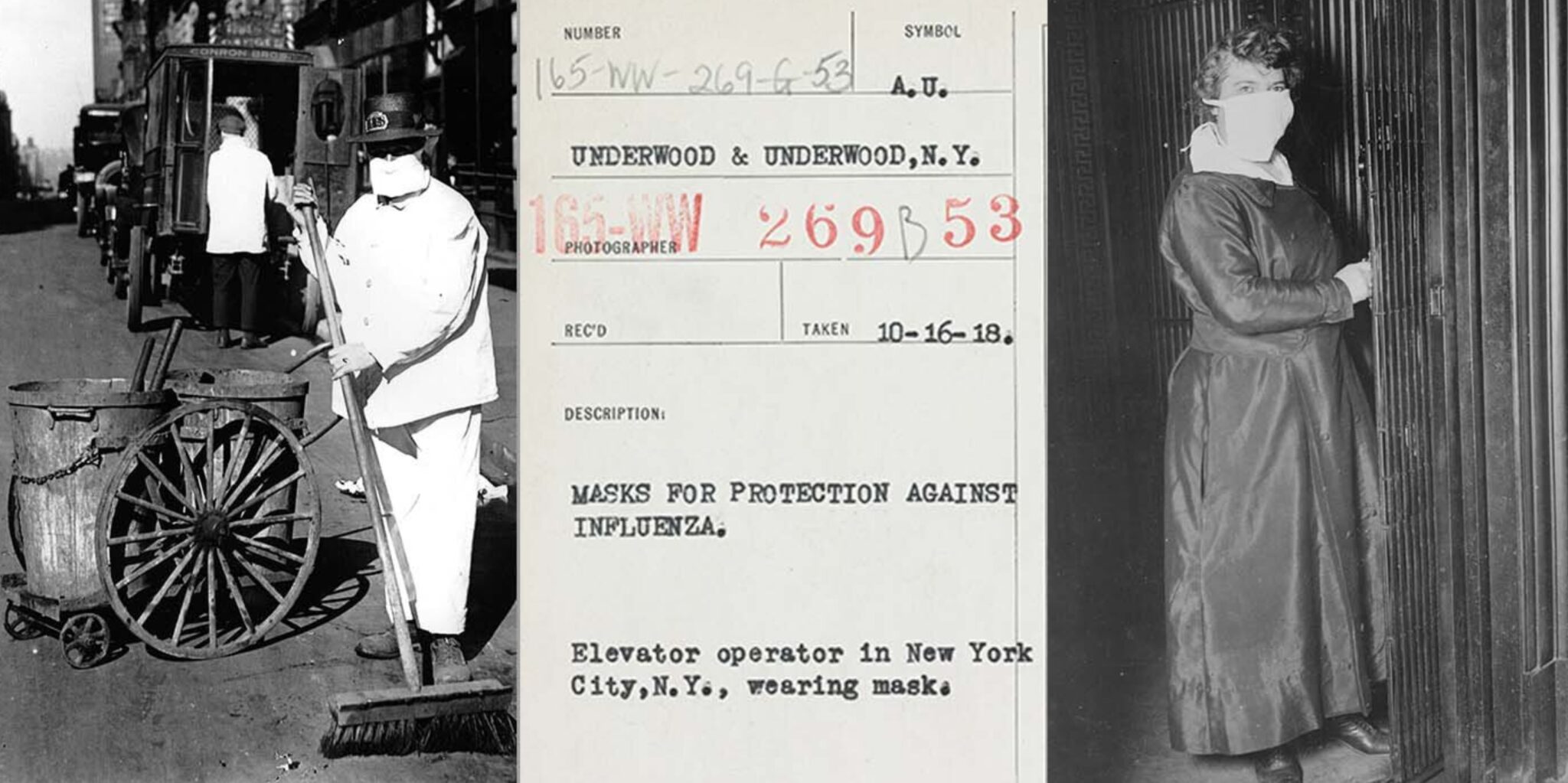

In any case, the borough expanded its capacity for disease surveillance through doctor’s reports and health checks. A massive education campaign convinced Brooklynites to cover their coughs and sneezes and stop spitting. If the recommendations did not help, the locals were fined, especially for spitting in public places. The question was whether the authorities could fine residents for not washing their hands with soap. The response of local health officials relied on a combination of mandatory and voluntary measures to contain the spread of the disease.

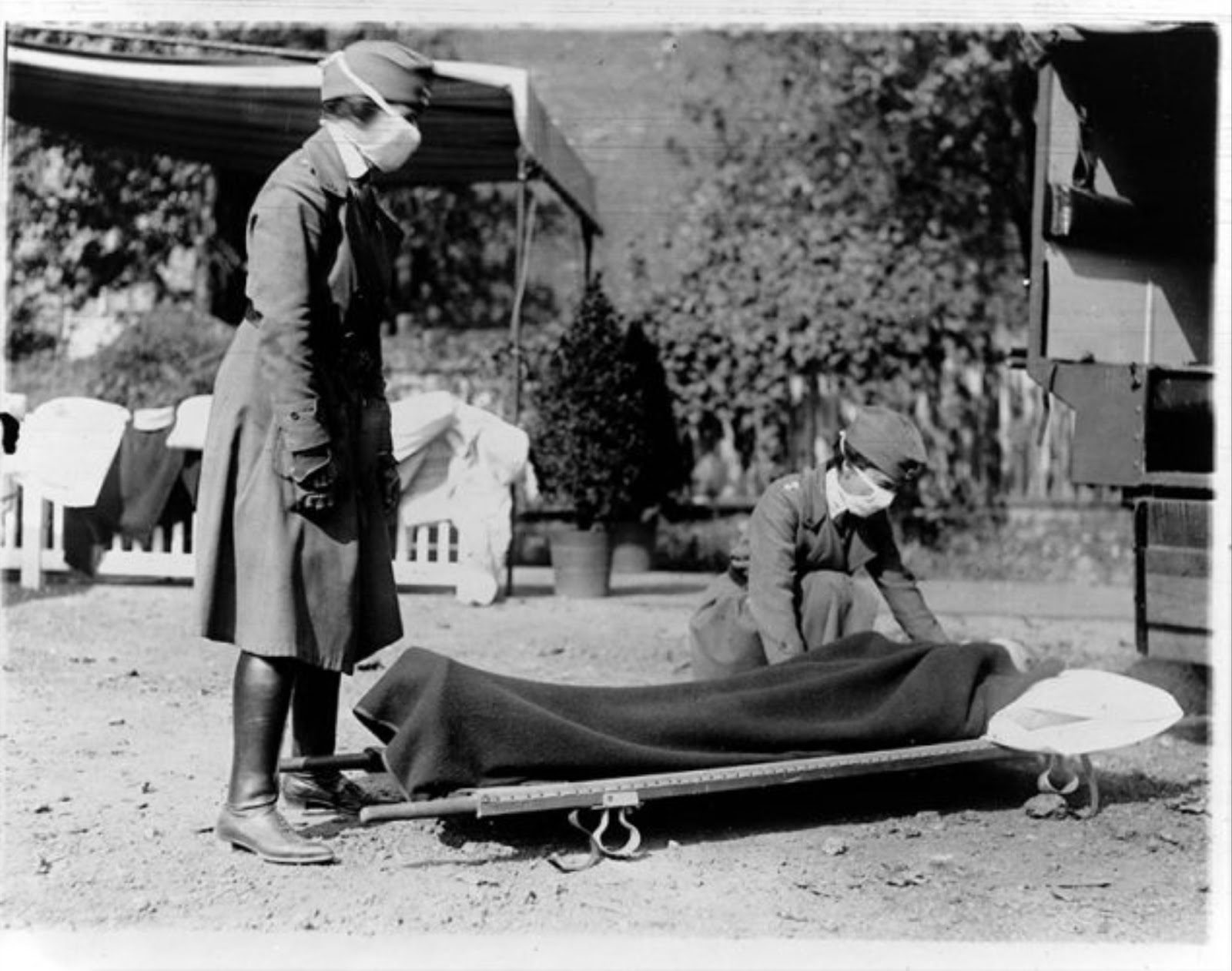

In addition, containment consisted of isolated quarantine for everyone who was already infected in their private homes. Those who lived in boarding houses or other non-private housing, mostly lower-class people living in more densely populated conditions, were moved to hospitals or temporary quarantine wards. These temporary wards were set up in gyms, armories and in the city’s first homeless shelter at the Municipal Housing Building on 1st Avenue.

One of the biggest problems for Brooklyn, as a part of New York, was public transportation. A program was implemented that required businesses to stagger their hours, trying to spread out traffic during rush hours and avoid large crowds. Schools remained mostly open. Each student was screened every morning and those with symptoms were sent home immediately.

Why didn’t they close the theaters?

Some considered this decision to be extremely controversial, as schools were a more sanitary environment than orphanages. By conducting daily surveillance, the spread of the virus could be slowed by keeping children in a safe and hygienic place every day. Schools were also used as primary distribution points for educational leaflets about the virus and the steps needed to protect themselves from it.

Brooklyn theaters were also closed, except for large, well-ventilated ones that followed strict health guidelines. In addition to the enhanced health guidelines, theaters were required to reduce crowding, ban smoking and not allow children under twelve to attend. All establishments that did not meet these standards were closed. This was done to not only allow people to share information but also to prevent the public from panicking.