It all started with the daguerreotype. It is an early photographic process invented in 1839 by Parisians Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and Joseph Nisefour Niepps. It was quickly adopted as a portrait medium in the United States of America. Daguerreotype portraits were especially popular in New York City, as well as in Brooklyn. The first American commercial portrait studio opened there in 1840. It is an interesting fact that by 1853 there were more daguerreotype studios in the city than in the whole of Great Britain.

The main reason for this popularity was that daguerreotypes were inexpensive compared to traditional painted portraits. This made it possible for a much larger number of consumers to have their image taken. Moreover, the daguerreotype created very similar portraits, which impressed people. Therefore, many of them considered the process of daguerreotyping mysterious and amazing. Read more about the development of photography in Brooklyn on i-brooklyn.com.

The emergence of photography in the United States

Photography came to the United States in the fall of 1839. It was then that information about Louis Jacques Mande Daguerre’s amazing invention, which allowed one to create one’s own portrait on a sensitive plate of silvered copper, came to America from distant France. This new technology fell into the hands of real craftsmen who quickly improved the whole process. For example, the exposure time was reduced so that the camera could capture not only stationary objects but also portraits of people.

Indeed, more than 95 % of American daguerreotypes, the most common form of photography at the time, namely from 1839 to the late 1850s, were portraits. Since the daguerreotype process did not involve a negative, each daguerreotype was a unique image.

In 1853, at the peak of the daguerreotype’s popularity, Americans produced about three million portraits in this way. Photographic portraits became common objects of middle-class life. And what is especially gratifying is that photographic technologies in the middle and late nineteenth century did not stand still, they developed rapidly, and each new breakthrough allowed photography to be used in new areas.

Thus, in 1856, a method was developed for making tintypes, i.e. unique images on inexpensive metal plates. This further reduced the price of photographs and led to the emergence of a reliable type of image that could even be sent by mail. Even more importantly, the increasing use of the so-called «wet plate» negative process in the late 1850s greatly facilitated the creation of glass negatives, which in turn enabled photographers to print a theoretically unlimited number of positive prints on paper.

The first portraits

But the most commercial use of the daguerreotype in those days was the production of photographic portraits. As a result, photo salons began to appear in Brooklyn. After all, the process of daguerreotyping usually caused discomfort to the client, which complicated the photographer’s work. After all, it is obvious that a portraitist could create any attractive portrait to please a client, while a daguerreotype captured what he saw.

And since clients were usually nervous before the photo, afraid that the photographic technology would reveal their every grimace and flaw, photographers had to make an effort to calm them down. Moreover, depending on the lighting conditions, daguerreotypes could require long exposures, which was even more difficult for the client, who had to sit still for quite a while.

Although technical inventions also came to the rescue here. For example, the photographer had a special vice-like clamp at his disposal to help hold the model’s head still. Of course, it was not about convenience, but art, as we know, sometimes requires certain sacrifices.

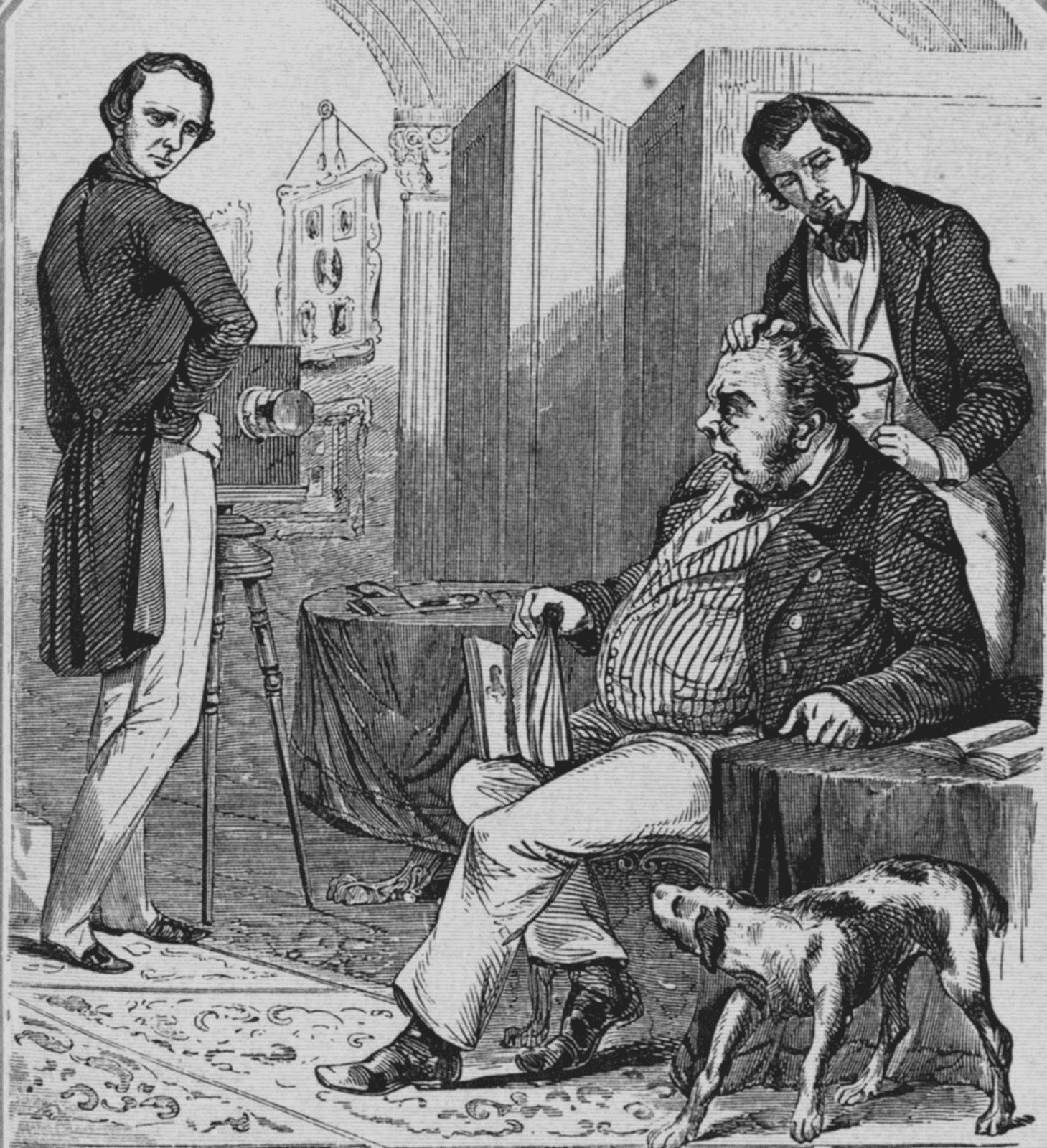

In general, the relationship between the model and the cameraman was quite tense in those days. Various caricatures on this topic were published in newspapers, even in the newspapers. There is a famous satirical image from 1850 called «Seating for a Daguerreotype», which comically depicts the process of shooting, where two cameramen seem to be quite rude while preparing the model to pose for a portrait.

There were also materials in the press that explained to both clients and photographers how to behave. In an 1851 article from the professional publication The Daguerreian Journal, the key element of successful portraiture was the operator’s pleasantness. According to this article, clients usually sat down to be photographed with a tired, worried, or thoughtless expression on their faces. At the same time, their main condition for a photo shoot was that the photo should be good.

Experts recommended that operators use their charm, tact, and charm to distract the client from gloomy thoughts, or with a pleasant conversation, an interesting story, etc. It was also recommended to use tips on how to behave, how to keep your head, where to go, etc., but they had to be delicate and timely. The main thing, the article says, is that in the end, it is desirable to bring the client to such a moral state that he or she has a cheerful and lively expression on his or her face.

Brooklyn photo masters

One of the most famous and successful Brooklyn photographers of that time was Joseph Hall. He built his photography business in Brooklyn after the Civil War. Before that, Hall was a chemistry major. But when Brooklyn, as well as the rest of New York, was caught up in the entrepreneurial spirit, he became a production photographer. What did this mean? Joseph Hall, he learned the skills and acquired the equipment to mass-produce carte de visite portraits and albumin prints for public consumption.

From the moment he began his business, Hall advertised his services and images in periodicals in Brooklyn. In particular, he offered his clients large 20×27 photographic compositions, such as his 1868 work Washington as a Freemason. It depicted the actor as the first President of the United States. He was wearing an apron and a belt.

In addition, Joseph Hall followed the example of Civil War photographers by outfitting a mobile van to be able to transport his camera and set it up in various locations. He took pictures of individuals and groups of people in the open air.

Sport and art in photography

Hall’s genius also included sports angles. He was considered the leading photographer of professional baseball teams, photographing the players. His large-format plein air photographs of various teams in uniform in baseball stadiums became the most commercialized depictions of the game in the late nineteenth century. A minimum of $5,000 per image was offered for such pictures.

Most of them were taken in 1888. The individual player portraits from the «Old Judge» series of cards are among the finest of the dead ball era. They were taken when visiting teams played against New York teams and developed in his Brooklyn studio at 349 Fulton Street.

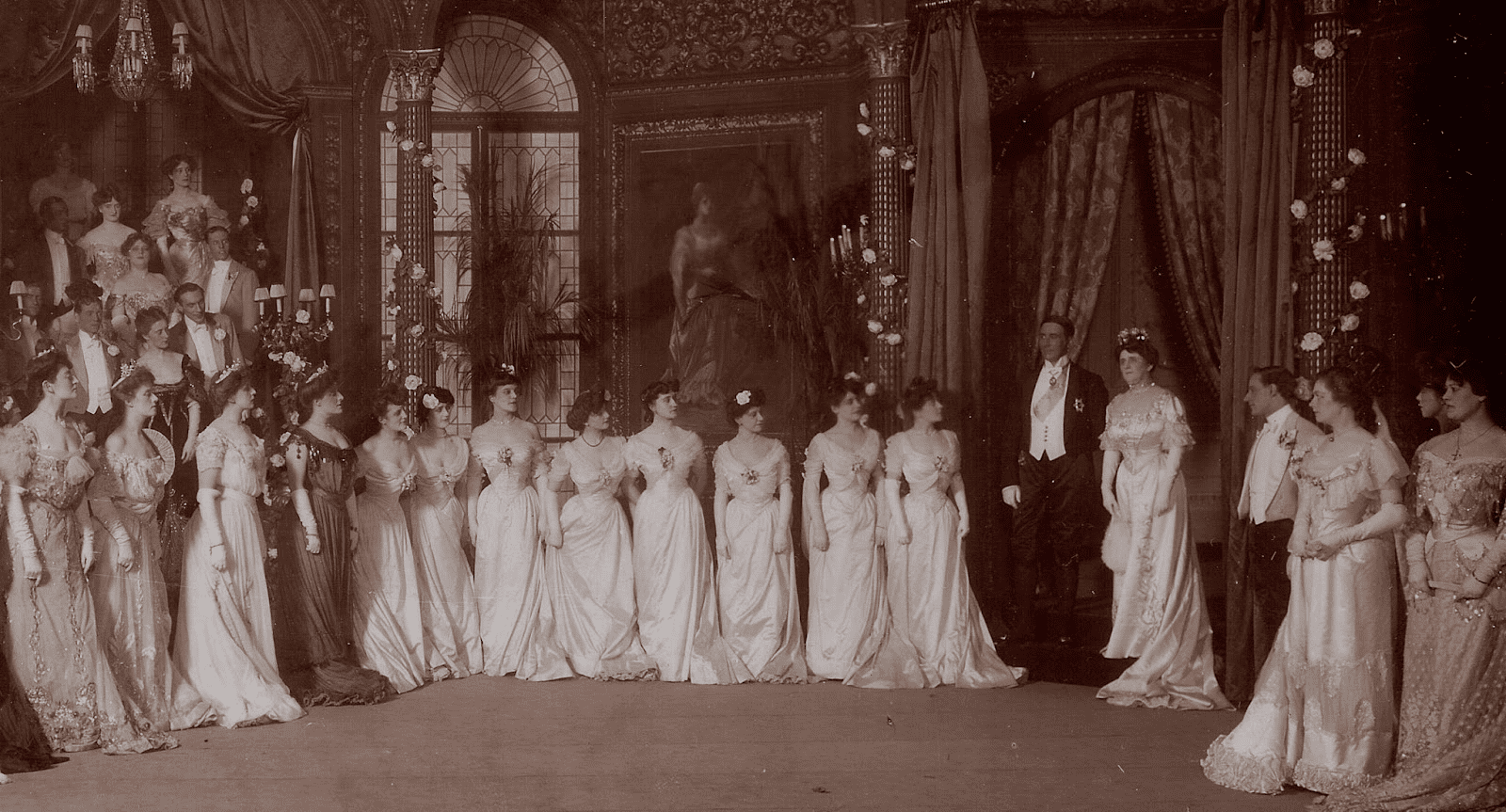

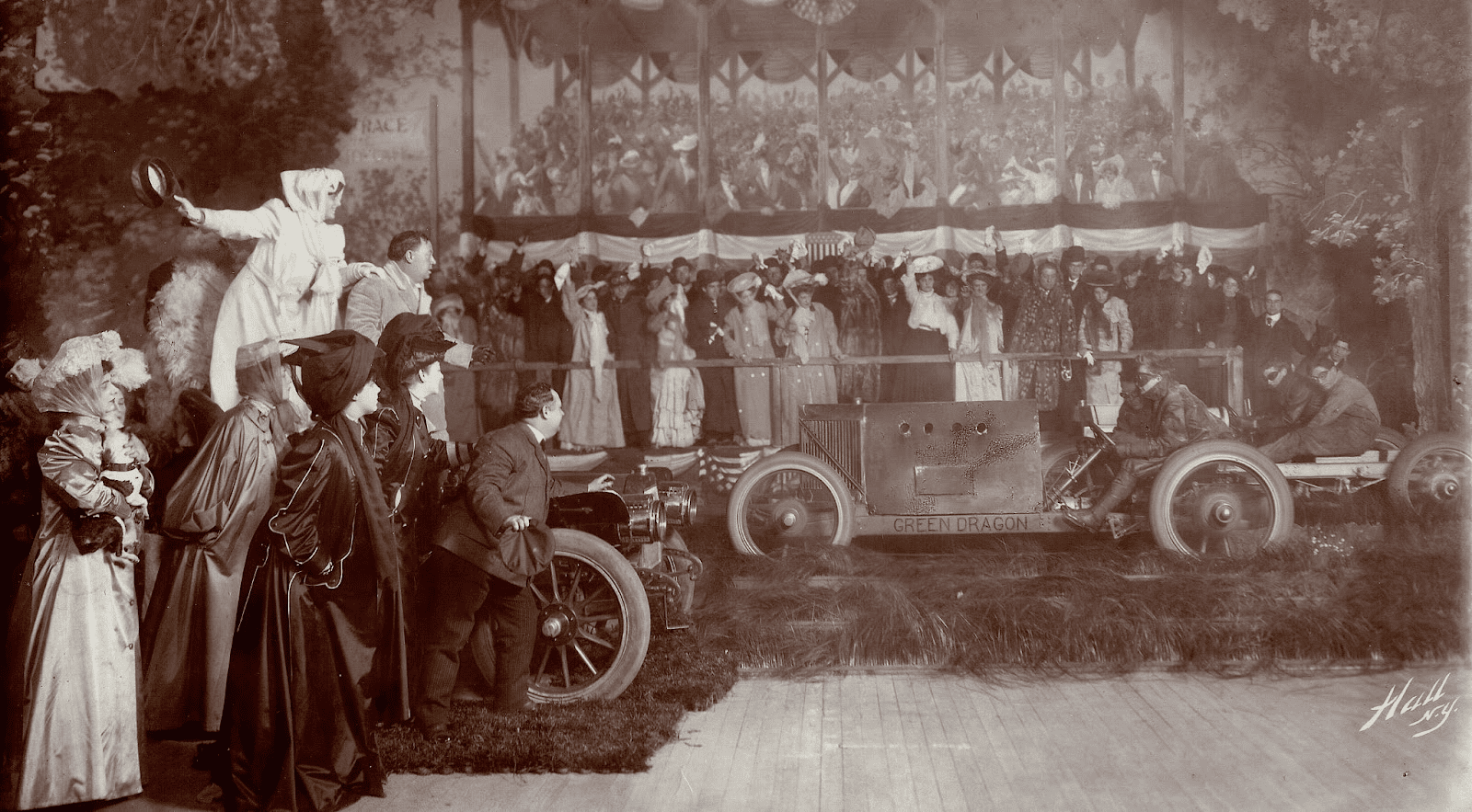

To better capitalize on the commercial photography market, Hall moved from Brooklyn to Manhattan, establishing a gallery on the corner of Broadway and 34th Street. From 1893 to 1905, he photographed many of the important dramas, operas, and musical comedies in New York City. His catalogs of images from the period 1905–1910 were unique in that they offered images identified by play title rather than performer.

Sources: