How is DNA originated and developed? Can it be cloned? How to create life in a Test Tube? These are the main questions of genetic scientists. Arthur Kornberg was the person who was very close to finding the answers. Find out more at i-new-york.

Matchbox collection

Arthur Kornberg was born in Brooklyn in 1918. His parents were immigrants from Polish Galicia. Arthur was the youngest of three children. The family owned a small shop selling tools and household goods. The future scientist did well in school and even skipped a few grades. But he did not have any scientific interests, neither for natural studies or the animal world nor for chemistry. Young Arthur had a strange collection of matchboxes.

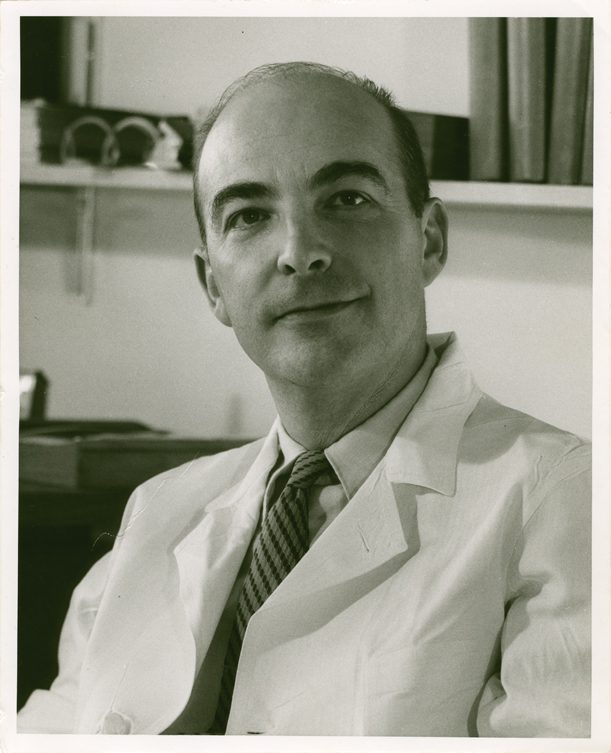

When the Great Depression struck, Kornberg took a practical approach to deciding on a profession. He enrolled in medical school. Back in high school, Kornberg was good at chemistry, besides, learning always came easy for him. In 1941, he earned a doctorate from the University of Rochester. Even then, he did not imagine himself in the world of great science.

During World War II, Kornberg served as a doctor on a US Coast Guard ship. Although he did get along with the ship’s captain, he still stayed on board throughout the war.

Kornberg occasionally wrote medical articles and sent them to various scientific journals. One of his articles, published in 1942, drew the attention of the scientific world. The article was about a study on the causes of jaundice outbreaks after vaccination against yellow fever. Back in medical school, he conducted research on Gilbert’s syndrome (it had a different name then). Rolla Dyer, the director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), hired him as a researcher in the nutrition laboratory.

Study of rats

After starting work, Kornberg conducted his first research on vitamin deficiency in rats induced by sulfonamides. Kornberg studied the influence of antibiotic-sulfonamides on the health of the experimental animals. They were first kept on a healthy diet and then given the drug, observing its deleterious and deadly effects. However, it was discovered that the consequences of the substance were not as severe and irreversible if rats were fed their regular food. The salvation itself lay in folic acid, as they are very similar in structure to the drug. It was found later that vitamin K is important in this process.

Kornberg paid great attention to the study of the mechanisms of vitamins. He saw that many vitamins trigger glycolysis and generally improve metabolic processes. To deepen his knowledge in this area, Kornberg asked to work with Bernard Horecker.

Together, they studied succinic acid. At that point, he realized that he lacked expertise in enzyme purification. So, he went to New York University. In 1947, he worked at the Washington University in St. Louis with future Nobel laureates Carl and Gerty Cori. Together, they researched pyrophosphates, but it was not clear to him at first. He clarified the details that he could grasp in Cori’s laboratory only after returning to the NIH. He made several important steps in the advancement of enzymology for which he received the Paul-Lewis Award (Pfizer Prize).

Introduction to DNA

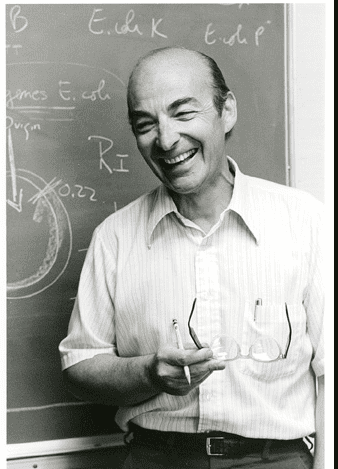

At the beginning of the 1950s, Kornberg was already a well-known biochemist. He tried in every way to push scientific boundaries. It occurred to him that nucleic molecules of DNA and RNA could be synthesized by the same method as the ones he studied earlier. At the time, other scientists were working on the structure of DNA. They knew what DNA was made of, but they did not comprehend how it was built. Scientists could not unravel the secret of the process of DNA formation from cells. Kornberg guessed that they are synthesized in cell enzymes that connect all nucleotides and was thinking about how to create them. After that, he left the NIH to delve into new research. For this reason, he went to the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. He was assisted by a whole team of students and colleagues. All of them worked on studying enzymes and DNA synthesis. Step by step, Kornberg identified new enzymes essential for DNA formation.

In 1956, Kornberg succeeded in synthesizing DNA using polymerase. He described this result in some articles. Some colleagues criticized him and claimed that it should not be considered full-fledged DNA. Others argued that genetic activity is important for DNA. This is what distinguishes DNA from the so-called result of Kornberg’s work, polydeoxyribonucleotides. Nevertheless, the first synthesis of DNA earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1959.

Life in the Test Tube

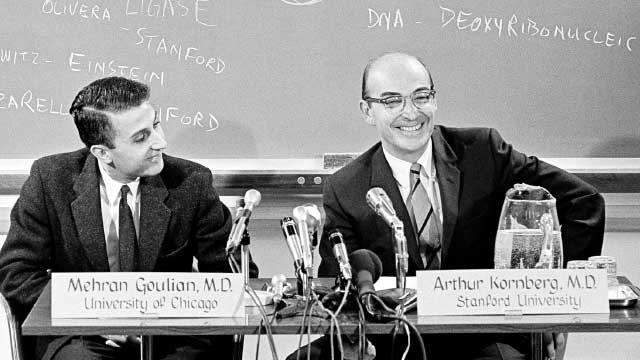

In 1959, Arthur became the head of the Department of Biochemistry at the Stanford University School of Medicine in San Francisco. He was provided with plenty of opportunities for work and research. He even hired a team of scientists to further study the synthesis of DNA with genetic activity. Arthur tried different variations of bacteria in new tests. This was much more challenging than anything he had ever done before which only motivated Kornberg. He began to experiment with small bacterial viruses (phages), hoping that they would not damage DNA matrix molecules. In 1967, Kornberg succeeded in synthesizing DNA phi X174.

A scientific press conference was held on this occasion. It was a major step in the world of science. But during a press release, Stanford’s information bureau immediately stated that they are not talking about “creating life in a Test Tube.” Nobody talked about human DNA, the issue was a viral one which is not viable outside of a large system. Yet, the media made a fuss about it.

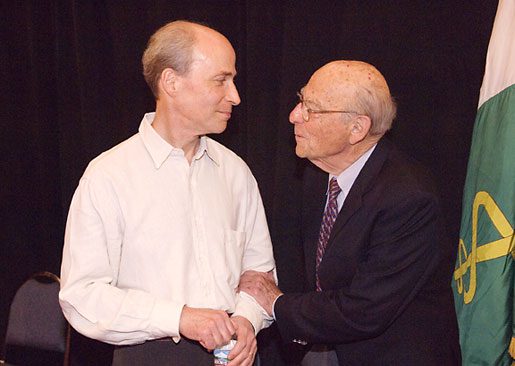

After this, Kornberg himself accidentally questioned his own findings. The DNA polymerase he had discovered raised questions about whether the enzyme was actually responsible for DNA replication. These doubts only intensified. John Cairns discovered a mutant E. coli that could reproduce without Kornberg’s enzyme. In 1971, Tom Kornberg, Arthur Kornberg’s son, who also became a scientist, refuted Cairns’ result. Tom made many great scientific discoveries in the future. Although he, like his father, did not initially consider a career in science.

“Building” the century

Many scientists were seeking an answer to the main question: How is DNA built? Kornberg was one of them. In 1967, his team agreed that DNA polymerase could be the starting point and foundation for the origin of a new chain. However, this thought turned out to be wrong.

They were trying to figure out what happens after parental DNA separates and a child’s DNA strand forms. One of Kornberg’s team members discovered his own enzyme, the Okazaki Fragment. They believed that it was this enzyme that helped create a new chain. But they couldn’t find all the pieces of the puzzle. To solve this, Kornberg returned to his studies of tiny bacteriophages Phi X 174 and M13. The team spent almost 20 years examining processes in the replication fork. It was revealed that seven different enzymes and a multi-component enzyme are involved in replication. Thus, they learned the composition of a new DNA strand.

They then began to study the chemical mechanism that triggered the creation of new DNA. They found the answer to what everything is made of but a new question arose: what does it all start with? This became important information for many genetic engineers.

Even though Kornberg’s discoveries were amazing, he encountered problems with industrial and pharmaceutical companies. He was concerned that companies would stifle the flow of information for the sake of profit. Numerous companies asked Kornberg and his colleagues to buy patents. Nonetheless, they always refused because they knew that their scientific freedom would end there. The secret of DNA creation is precious, but scientists still declined the offer. After all, the freedom of scientific decisions was more significant.

In the 1980s, Alejandro Zaffaroni approached Kornberg with a proposal to work at his research institute. More precisely, establish it. Zaffaroni himself was a biochemist and an ardent proponent of science and scientific progress. This is how Kornberg and his colleagues founded DNAX, which became a leading institute for molecular and cellular biology in America. In 1981, it was purchased by Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals and became part of Biopharma. The main focus of research was in the fields of immunology and oncology. Kornberg remained at the company and helped to recruit new scientists to the team. He continued his work on DNA until his death in 2007.